You would be forgiven for thinking that wireless mesh networking is just another marketing bullet point for new Wi-Fi routers, a phrase coined to drive up prices without delivering benefits. But we can avoid being cynical for once: mesh technology does deliver a significant benefit over the regular old Wi-Fi routers we’ve bought in years past and that remain on the market.

Mesh networks are resilient, self-configuring, and efficient. You don’t need to mess with them after often minimal work required to set them up, and they provide arguably the best and highest throughput you can achieve in your home. These advantages have led to several startups and existing companies introducing mesh systems contending for the home and small business Wi-Fi networking dollar.

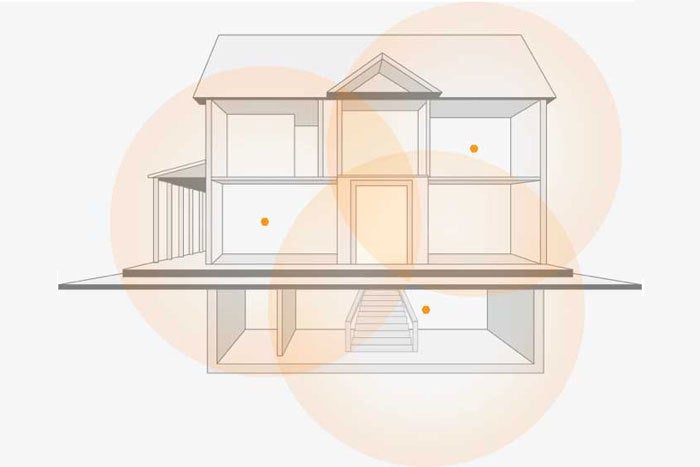

Mesh networks solve a particular problem: covering a relatively large area, more than about 1,000 square feet on a single floor, or a multi-floor dwelling or office, especially where there’s no ethernet already present to allow easier wired connections of non-mesh Wi-Fi routers and wireless access points. All the current mesh ecosystems also offer simplicity. You might pull out great tufts of hair working with the web-based administration control panels on even the most popular conventional Wi-Fi routers.

What mesh means

The concept of mesh networks first appeared in the 1980s in military experiments, and it became commercially available in the 1990s. But hardware, radio, and spectrum requirements; cost; and availability made it truly practical for consumer-scale gear only in the last couple of years. That’s why we’re seeing so many systems hit the market all at once.

Mesh networking treats each base station as a node that exchanges information continuously about network conditions with all adjacent nodes across the entire set. This allows nodes that aren’t sending and receiving data to each other to still know all about each other. This knowledge might reside in a cloud-based backend or in firmware on each router.

Mesh networks don’t retransmit all the data passing through among a set of base stations. The systems on the market dynamically adjust radio attributes and channels to create the least possible interference and the greatest possible coverage area, which results in a high level of throughput—far higher than anything that’s possible with WDS (Wireless Distribution System) and similar broadcast-style systems.

The principle behind all wireless networking is “how do I transmit this number of bits in the smallest number of microseconds and get off and let someone else use it?” explains Matthew Gast, former chair of the IEEE 802.11 committee that sets specs used by Wi-Fi. Mesh networks manage this better than WDS.

In some cases, Gast notes, a mesh node might send a packet of data to just one other node; in others, a weak signal and other factors might route the packet through other nodes to reach the destination base station to which the destination wireless device is connected.

Some mesh routers have single-band-at-a-time radios, and are meant more as smart extensions. But it’s more common that the nodes have radios for two or even three frequency bands, like the latest Eero. This lets mesh dedicate bands to intra-node data, switching channels to reduce congestion, or mixing client data and “backhaul” data on the same channel.

The ultimate goal is to make sure as much throughput remains reserved for actual productive traffic, such as streaming 4K video from one end of a house to the other or making fast connections to internet multiplayer games, relative to that consumed by moving data around the network.

If a node is powered down or crashes—your cat gets a little too interested and knocks one off a shelf—the network doesn’t go down, too. As long as every node can continue to communicate with at least one other node, you still have a fully functioning network.

You typically rely on a smartphone to help set up the first node and network parameters and add additional nodes to an existing network. Because you don’t have to plan where mesh nodes go, mesh systems automatically reconfigure as you add nodes. Most of the systems available offer help in figuring out where to locate units, some of them using indicators on the nodes themselves while others require smartphone software. “There is an immense amount of engineering effort to make something very simple,” says Gast.

Is it smart to invest in mesh?

The price you pay for this better efficiency? Proprietary protocols. While Wi-Fi remains standardized, and extremely and reliably compatible among equipment from different makers, no two mesh systems on the market work with each other. An early mesh protocol, 802.11h, wound up being not just insufficient to the task, but entirely ignored by companies as they pursued better results and competitive advantages. It’s also unlikely that any time in the next few years a compatible industry standard would arise and get uptake, given no such standard is currently working its way through the pipeline.

You have three reasons to want compatibility: a way to acquire cheaper equipment if one manufacturer charges more than you want to pay for additional nodes; as an escape route if a company or product line goes under; or as a way to upgrade a network gradually to incorporate new standards. That’s not possible with mesh.

Being locked in to one manufacturer increases risk, because several companies making mesh gear—Eero, Luma, and Securifi—are startups, and not all startups succeed. More established firms, such as D-Link, Linksys, Netgear, and TP-Link, make mesh networking hardware, but if those product lines don’t produce profit, they won’t continue to make units forever.

All of this could affect you in six ways:

- Inability to get technical support when something goes wrong.

- Lack of warranty coverage for failed hardware. (Companies in bankruptcy, however, might be required to fund some amount of repair and replacement.)

- No way to purchase new units to expand your network.

- Smartphone apps, which some systems rely upon exclusively, stop receiving updates and stop working.

- Cloud-based elements for configuration and management get turned off, rendering the nodes inoperable or locked into the last configuration. A Wi-Fi camera memory card maker at one point intended to disable configuration updates to its cloud-linked product. This can be an issue even with active products: Google accidentally reset its non-mesh OnHub and mesh Google Wifi routers in February because of a cloud-based account login issue.

- Critical security flaws are discovered, but can’t be updated. While it seems unlikely that a mesh device that didn’t sell enough to be a success would be exploited, most standalone hardware of any kind—from DVRs to internet-connected cameras—use a variation of Linux and one of a handful of widely used chipsets.

Balanced against this is the lifecycle of Wi-Fi routers. In my nearly 20 years of buying and testing wireless networking hardware, I’ve found that it either fails in three to five years or needs an upgrade in that time to take advantage of newer networking features. Consider the price tag on a mesh system your rental price across that period, and think about whether the value of $70 to $150 a year, depending on the system and number of nodes, delivers enough utility. If you’re lucky, it will last much longer.

Weaving a finer mesh

The future of mesh isn’t more and more and more nodes. Rather, it’s nodes that have more and different kinds of radios and other features built in. Already, some mesh nodes have Bluetooth for configuration and personal area networking control and up to three Wi-Fi radios supporting the full 802.11a/b/g/n/ac range.

Future nodes could add more radios or slice-and-dice an 802.11ac Wave 2 feature that allows beamforming and device targeting to further separate intra-node traffic from device-to-device traffic. And they could throw in 802.11ad/Wi-Gig for superfast ultra-high-definition streaming or ZigBee and other smart-home standards.

But the baseline set already today is for fast, efficient, and simple. Newer nodes can put more icing on the cake.

Luma Home, Inc.

Luma Home, Inc. Luma Home, Inc.

Luma Home, Inc.